Which Was The First Class Of Animals To Move From Water To Land

Special Issue: Textile Cultural Development

- Original Scientific Article

- Open Admission

- Published:

Early Terrestrial Animals, Evolution, and Doubt

Development: Didactics and Outreach volume 4,pages 489–501 (2011)Cite this commodity

Abstract

Early terrestrial ecosystems record a fascinating transition in the history of life. Animals and plants had previously lived but in the oceans, merely, starting approximately 470 million years ago, began to colonize the previously arid continents. This paper provides an introduction to this period in life'south history, beginning presenting background information, before focusing on one creature group, the arthropods. It gives examples of the organisms living in early terrestrial communities and and then outlines a suite of adaptations necessary for survival in harsh terrestrial environments. Accent is placed on the role of uncertainty in science; this is an integral part of the scientific process, still is frequently seized upon by god-of-the-gaps creationist arguments. We hope to illustrate the importance of both uncertainty and scientists' freedom to express doubt while a consensus is being built.

Introduction

The impetus for this paper comes from a media written report on the inquiry of Garwood et al. (2009). The piece in question—in one of the more widely circulated merely less universally respected newspapers of the Uk—outlined the three-dimensional reconstruction of Carboniferous arachnids. Though the reporting was for the most role scientifically accurate, the associated online comments section provided unfortunate contrast. The get-go entry was a typically petty and superficial anti-evolutionist'southward jibe regarding these arachnids: "they look just like spiders do today. 300 million years and no change. […] Kind of hard on the old evolution theory isn't information technology?" When the comment's author was asked to expand on his beliefs, the response was an entirely anticipated: "Why do I take to come with an alternative for your useless theory?"

This altercation encapsulates perfectly a mutual creationist mindset, one based on brief (and often incorrect) observations coupled with complete ignorance (or at best patchy agreement) of the scientific context framing an argument. See, for example, the myriad arguments introduced in Part III of Scott (2009). It further relies upon a god-of-the-gaps statement, the belief that in the case of unanswered questions the proponent's personal worldview wins past default. No alternatives nor evidence supporting the proponent'south perspective are required (Pennock 2007). The comment is flawed on a number of counts. Not least, the arachnid group in question, the trigonotarbids (Fig. 1), were indeed quite different from spiders in that they lacked the power to spin silk (Shear 2000a) and possessed a segmented posterior body region (likely inherited from their last shared common antecedent with spiders; Dunlop 1997). Furthermore, every bit we shall see subsequently in this article, a degree of morphological stasis over 300 meg years is in no way antithetical to the theory of development. The comment is also unfortunate because the early terrestrial (state-based) animal communities in which this trigonotarbid lived provide the states with resounding evidence for development. They as well offer an splendid example of the unanswered questions and uncertainties inherent to—and a driving force in—scientific inquiry. It is these uncertainties that the arguments of antievolutionists seize upon. If they succeeded, this would stifle the colorful globe of scientific discovery and reduce it to a Manichaen palette of unquestioning certainty and unknowable unknowns (the dualism of Nelson 1999).

A computer model of the trigonotarbid arachnid Eophrynus prestvicii (Garwood et al. 2009) from the Late Carboniferous Coal Measures, Britain. Reconstruction from a CT scan conducted at the Natural History Museum, London, U.k.. Fossil housed at Lapworth Museum of Geology, Birmingham, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, 30 mm in length

With this in mind, we hope that this paper will not only introduce these fossil communities and outline their evolution, but likewise demonstrate that ambiguity in science is neither detrimental nor a weakness. Rather it is a vital part of our field, which stimulates argue and drives further research and discoveries.

The paper is carve up into sections—the side by side will introduce terrestrial life as a whole during this menses in the Earth's history before we focus on one group of animals in detail, the arthropods. We will then introduce examples of early terrestrial fossils that run the gamut from entirely extinct groups to those that are largely unchanged compared to their modern relatives, living in ecosystems that closely resemble those today. We will finish by introducing some of the adaptations these animals accept evolved for a life on state.

Terrestrial Palaeozoic Life

The Paleozoic Era lasts from the first of the Cambrian Period (542 million years ago; Gradstein et al. 2009), known for its famous explosion of marine animals, to the end of the Permian Catamenia (251 meg years ago); marked past the greatest mass extinction ever known (Sahney and Benton 2008). Prior to the Paleozoic, the only life on country was unicellular, a fact that—until recently—could just exist inferred from indirect evidence (Rasmussen et al. 2009; Prave 2002). However, current research is revealing unexpectedly various terrestrial communities revealed in 1 billion-year-old cellular fossils (Strother et al. 2011). It was during the Paleozoic Era that plants (showtime known from microfossils called cryptospores that appear in the mid-Ordovician, nigh 470 million years ago; Wellman and Gray 2000) and animals (known from Silurian fossils, at least 423 meg years agone; Wilson and Anderson 2004) began to colonize the land. Land plants started as modest, non-vascular mosses and liverworts (bryophytes; Edwards 2000), but past the Late Silurian, uncomplicated plants with axial organization and last sporangia (spore-bearing structures) were condign common (e.one thousand., Cooksonia; Kenrick and Crane 1997). During the Late Paleozoic—the Devonian (416–359 one thousand thousand years ago) and Carboniferous (359–299 million years agone) periods—the beginning widespread woods ecosystems became established (DiMichele et al. 2007). Although quite unlike from modernistic forests, by the Carboniferous, these were diverse (DiMichele 2001) and included early tree-like relatives of extant club mosses (lycopsids) and horsetails (Calamites), and a broad variety of ferns (Falcon-Lang and Miller 2007). These forests were dwelling to a broad range of animals, which had first ventured on to land in the preceding 100 1000000 years. Ane grouping of these were early ancestors of all terrestrial vertebrates, which had first ventured on to country during the Devonian (probably betwixt 385 and 360 million years ago). Paleozoic fossils record this transition from fish to land-dwelling limbed organisms (tetrapods; Clack 2009) and too bridge the split betwixt true amphibians and other vertebrates (mammals and reptiles/birds; Clack 2006; Coates et al. 2008). Many early tetrapods were still aquatic, and probably lived within rivers and other freshwater environments, with the possible occasional foray onto land (Benton 2005). Fully terrestrial species were mutual by the Carboniferous Period, withal, and the primeval true reptiles had evolved past the cease of the Paleozoic, in the grade of small- to medium-sized insect eaters (Modesto et al. 2009).

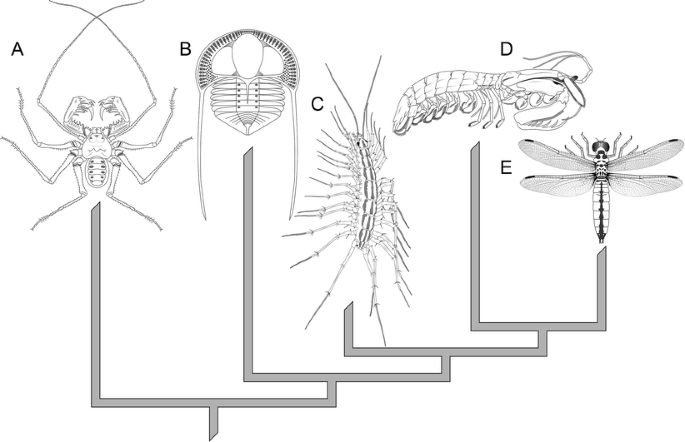

The bulk of fauna diverseness and abundance in Paleozoic terrestrial communities tin can be plant in the arthropods (a group which has, in fact, been dominant in terms of animal species diversity for all of the past 520 million years; Edgecombe 2010). The phylum Arthropoda is a grouping of animals united by, amongst other traits: external and internal body sectionalization with regional specialization (tagmosis, e.grand., a thorax with legs and wings versus a limbless abdomen in the case of insects); an exoskeleton composed of articulated plates, hardened through calcification or sclerotization (protein cantankerous-linking); body segments that primitively behave paired, articulated appendages; growth via molting (ecdysis); a pair of lateral facetted (compound) eyes that are innervated past the first of three segments that comprise the encephalon; and an open circulatory system featuring a dorsal centre with lateral valves (Grimaldi and Engel 2005). The unique features of arthropods indicate that they are a monophyletic group (descendants of a common ancestor that possessed the diagnostic features of the group). Arthropoda (Fig. 2) includes the extinct trilobites, the insects, the myriapods (millipedes, centipedes, and relatives), the crustaceans (east.grand., crabs, lobsters, shrimp), and the chelicerates (arachnids, such as spiders, scorpions and mites, and horseshoe crabs). Their abundance makes arthropods ecologically vital; for case, myriapods are important processors of leaf litter in forests, and termites swallow large quantities of cellulose (Crawford 1992; Higashi et al. 1992). Without arthropods, the life and ecosystems of the Earth would be radically different. Their astounding diversity (constituting in excess of 75% of all described living species; Brusca and Brusca 2003) can help elucidate the patterns and processes of evolution. For example, the study of trilobites was fundamental to the evolution of punctuated equilibrium as a model for evolutionary alter (Eldredge and Gould 1972; Gould and Eldredge 1977), and the fruit fly Drosophila was the "model organism" used in much of the pioneering work on genetics in the early twentieth century as well equally unraveling the genetics of development in the late twentieth century. Information technology is for these reasons that the following give-and-take of terrestrial Paleozoic life and evolution will focus on the Arthopoda.

Diagram showing the best supported evolutionary relationships of the v arthropod groups: chelicerates (a) (hither represented by an amblypygid arachnid), trilobites (b) (a member of the family Trinucleidae), myriapods (c) (scutigeromorph centipede S. coleoptrata), crustaceans (d) (a stomatopod or mantis shrimp), and insects (e) (a dragonfly)

The Palaeozoic Fossil Record of Terrestrial Arthropods

The showtime terrestrial arthropods predated tetrapods by tens of millions of years (Shear and Selden 2001). Bear witness of animal life on land before the first known arthropod torso fossils can exist constitute in the course of preserved traces that are probable to have been created by macroscopic organisms. Identifying the animal that made trackways or burrows is not e'er straightforward. For example, burrows assigned to the ichnogenus Scoyenia from Late Ordovician (ca 447 million years ago) rocks in Pennsylvania (Retallack and Feakes 1987) had been interpreted every bit having been made by millipedes (Retallack 2001), but this has been disputed based on how living millipedes burrow (Wilson 2006) and also because the sediments show show of a marine rather than terrestrial origin (Davies et al. 2010). The best candidates for trackways of Ordovician age that were made past an identifiable group of terrestrial arthropods occur in Late Ordovician rocks in Cumbria, UK, in ash and sandstones that were deposited subaerially (Johnson et al. 1994). A comparison with the locomotory traces of living "pivot cushion" millipedes showed that the stepping gait of the Cumbrian Ordovician trackways is consistent with them having been made past an early on millipede (Wilson 2006).

The first torso fossil bear witness of the animals responsible for such tracks dates from the Silurian Flow (444–416 million years ago). Several millipedes have recently come to calorie-free from Stonehaven, Uk (approximately 423 1000000 years ago), including one species, Pneumodesmus newmanii, that provides the first show for air breathing in any grade of animal (Wilson and Anderson 2004). This tin can be seen in spiracles (or, more than biblically, stigmata)—openings into the tracheal (breathing) system which are a terrestrial feature by definition. Some other of the Silurian millipedes has a paired structure on the anterior part of the body, in the usual segmental position and with a characteristic form of a gonopod, a modified pair of legs that male millipedes apply to transfer sperm to the female's genital opening (Fig. 3; Wilson and Anderson 2004). The Silurian fossils thus provide straight testify for a similar reproductive mode as their extant relatives.

Photograph and sketch of mid-Silurian millipede, Cowiedesmus eroticopodus (photograph courtesy of Yong Yi Zhen, Australian Museum). This, the front of the specimen, shows the head, collum (first segment behind the head, with no limbs), and and then the start of the torso. Too visible is a modified leg, mayhap associated with reproduction. Shown portion of fossil 12 mm in length. After Wilson and Anderson (2004)

The majority of fossils from around this time, all the same, are non discovered past simply splitting rocks in the field, but rather are found in acid macerate residues. These are "leftovers" from the acid digestion of rocks, to which the arthropod cuticle (exoskeleton), composed of chitin, is resistant. The earliest deposit from which this technique has recovered identifiable organisms is found in Ludford Lane, Shropshire, Britain (approximately 417 1000000 years agone) where both arachnids and centipedes are known (Jeram et al. 1990). A wider range of arthropods are recovered using this method from Centre Devonian (388 one thousand thousand years ago) rocks of Gilboa, New York. These include a number of different arachnids, including mites and pseudoscorpions (Shear et al. 1987; Norton et al. 1988; Schawaller et al. 1991; Selden et al. 1991), centipedes (Shear and Bonamo 1988), and possible fragments of insect exoskeleton (Shear et al. 1984).

Some other famous Devonian (approximately 396 1000000 years ago on the basis of radiometric dating, though spores suggest a slightly older age in the Early Devonian; Rice et al. 1995; Wellman et al. 2006) fossil locality is the Rhynie Chert, virtually Aberdeen, in Scotland. These translucent rocks were formed in a hydrothermal hot spring setting in which silica-rich water inundated and silicified nearby vegetation, including a number of the animals—all arthropods—creating a near-perfect record of this early terrestrial ecosystem (Trewin et al. 2003). The incredibly well-preserved fossils are studied in slides made from the stone and often brandish the internal anatomy (due east.grand., book lungs, the respiratory organs of arachnids; Kamenz et al. 2008). Animals described to date include arachnids (Fayers et al. 2005), primitively flightless hexapods (springtails and a bristletail or silverfish), also equally true insects (Fayers and Trewin 2005; Engel and Grimaldi 2004), centipedes (Shear et al. 1998), and freshwater Crustacea, including extinct relatives of fairy shrimp and polliwog shrimp (Trewin and Fayers 2007). Another fossil locality from the Early Devonian is Germany'southward Alken-an-der-Mosel, from which a range of unlike arthropods, including several kinds of arachnids and relatives of millipedes called eoarthropleurids, were described past the Norwegian paleontologist Leif Størmer (1970; 1972; 1973; 1974; 1976), but few other deposits preserve anything more than than isolated individuals. Despite the of import anatomical, ecological, and temporal information provided past the Silurian and Devonian fossil deposits, the first widespread and well-preserved record of terrestrial ecosystems dates from approximately twenty meg years later on, in deposits of the Upper Carboniferous Period (Shear 2000b). During this period, a mountain-building result, the Variscan Orogeny, contributed to the assembly of the supercontinent Pangea (Cocks and Torsvik 2006). Despite glaciations at the poles, a broad zone carpeted with thick forests and vegetation spanned the tropics and even some higher latitudes (Cleal and Thomas 2005). These forests supported diverse ecosystems (Shear and Kukalová-Peck 1990). Many of them were in consequence mires, wet environments in which organic matter accumulates (DiMichele 2001), and flooding was widespread (Falcon-Lang 2000; Plotnick et al. 2009). The resulting waterlogged boggy sediments create ideal weather for the preservation of fossils within siderite (FeCOiii) nodules and likewise for the germination of coal (Curtis and Coleman 1986). As a result, coal from this menstruation is institute throughout N America and Europe. In fact, the Carboniferous was responsible for fuelling the industrial revolution on both continents (Chandler Jr 1972; Hartwell 1967). Thus, a number of factors created ideal weather for both the widespread preservation of fossils during the Carboniferous and the exploitation of these deposits past geologists more than 300 million years later on. As a effect, they provide one of the most of import windows into early terrestrial ecosystems.

Evolutionary Relationships

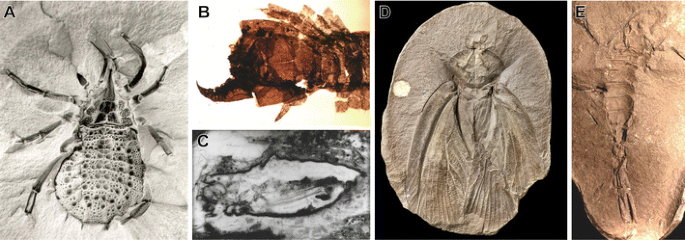

Fossils from these early ecosystems record a number of arthropod groups at different grades of organization, which we volition briefly compare here. Some are entirely extinct groups, such equally the aforementioned arachnids, the trigonotarbids (Fig. 4a; Dunlop et al. 2008a). These are known from uncommonly well-preserved Rhynie Chert fossils and appear to have been amid the nearly abundant arachnids in Carboniferous coal forests (Garwood and Dunlop 2011). The presence of ii pairs of lungs on the same trunk segments as some extant forms provides a strong statement that they are almost closely related to a group known as the tetrapulmonate arachnids, which includes the spiders, whip scorpions, whip spiders, and short-tailed whipscorpions (Dunlop 2010). Indeed, the fine structure of the volume lungs from a Devonian trigonotarbid, examined using three-dimensional reconstruction techniques, is shared with living tetrapulmonates (Kamenz et al. 2008). The youngest fossil fellow member of the group dates from 290 million years ago (Rößler et al. 2003). Thus, the trigonotarbids are an entirely extinct group, an evolutionary dead end, simply i that shares a common antecedent with spiders and other arachnids with ii pairs of lungs.

a Fossil of trigonotarbid arachnid, Eophrynus prestvicii, from the Carboniferous of the Uk (courtesy of Jason Dunlop). Fossil 30 mm in length. b The centipede Devonobius delta from the Devonian Gilboa eolith of New York State (Shear and Bonamo 1988). Shown portion of fossil ane.two mm in length. c The Devonian harvestman Eophalangium sheari from the Rhynie Chert (Dunlop et al. 2004). Fossil 6 mm in length. d Roachoid fossil Archimylacris eggintoni from the Carboniferous of the UK (Garwood and Sutton 2010). Fossil 41 mm in length. e Carboniferous scorpion Compsoscorpius buthiformis (Legg et al. 2011). Fossil 21 mm in length

The earliest centipedes showroom features that allow them to exist classified in some of the major groups that take survived until today. The oldest of these, from the Late Silurian of the Welsh Borderlands in England, belong to a genus, Crussolum, that is better known from various body parts in the Early and Center Devonian (equally for many examples in this article, the Devonian fossils come from the Rhynie cherts in Scotland and Gilboa in New York State—Fig. 4b has an example; Anderson and Trewin 2003; Shear and Bonamo 1988). Crussolum is unambiguously a fellow member of Scutigeromorpha, a group that includes 100 living species that more often than not alive in the torrid zone and subtropics, but best known from the "house centipede," Scutigera coleoptrata, an introduced species in many temperate parts of the world (Fig. 2c). Crussolum shares with the extant scutigeromorphs such features every bit a pentagonal cantankerous-department of the leg with each of the ridges that runs along the leg segments bearing a file of spines and thickened setae, but it lacks a few details that all of the living scutigeromorphs share with each other. For case, though the fossils have the kickoff pair of body legs modified into a functional part of the head (and housing the venom apparatus in all living centipedes), they do non accept long "spine bristles" in fixed positions that are seen in all the living species. This mix of archaic and avant-garde characters in Crussolum is described using a convention called "stem groups"; Crussolum belongs to the stem grouping of Scutigeromorpha. This means that the species is more than closely related to Scutigeromorpha than to any other living centipede group, but it branched earlier than the most recent common antecedent of all living scutigeromorph species.

Amid the earliest winged insects—and very common in the Carboniferous—were the Blattoptera, or "roachoids" (Fig. 4d). As the name suggests, these were similar to modern-twenty-four hour period cockroaches. For example, they possessed hardened, protective forewings and a pronotum (a head shield originating at the starting time segment of the thorax), but unlike truthful cockroaches, they had a long needle-like ovipositor for laying eggs (Grimaldi and Engel 2005). The reason they are known equally "roachoid" fossils is because—while they are superficially similar to cockroaches in appearance—they predate the carve up betwixt the mantises and the cockroaches and termites (the termites are actually highly derived, eusocial cockroaches; Inward et al. 2007). As such, these weren't an evolutionary dead end; collectively, "roachoids" represent a class at the base of the evolutionary tree for Dictyoptera, the formal proper name for the mantises (and cockroaches + termites), making them another instance of a stem group form. It is likely that some of the later Carboniferous fossils postdate the evolutionary divergence of the extant lineages of Dictyoptera, and they would accordingly vest to the stem groups of either the mantises or the cockroach/termite co-operative (Béthoux et al. 2009).

Scorpions are the earliest known arachnids and take a meaning Paleozoic fossil record (Fig. 4e; Dunlop et al. 2008b). While debate remains regarding whether their earliest representatives were aquatic or terrestrial (Dunlop and Webster 1999; Kamenz et al. 2008), by the Carboniferous, there is little question the scorpions were state-dwelling (Jeram 1994a). Even by the Early Devonian, fragments of the book lungs of fossil scorpions signal air animate (Shear et al. 1996). All modernistic scorpions belong to a group known as the orthosterns, which possess spiracles within the plates on the scorpions' underside rather than at their margin as seen in some of the oldest fossil species. The oldest members of this group are Carboniferous in age (Fig. 4e; Vogel and Durden 1966; Jeram 1994b; Legg et al. 2011), and the oldest known member of an extant family is at least 50 million years younger (Lourenço and Gall 2004). Thus, later Paleozoic scorpions probably autumn in the stem grouping of modernistic families, just postdate the last mutual ancestor of the orthosternous scorpions. Nosotros tin can hence say that the origin of extant scorpions lies in the Carboniferous Menstruum.

Perchance some of the most impressive terrestrial Paleozoic fossils, however, are those of harvestmen (Fig. 4c): arachnids of the order Opiliones, which have a small fused body and oftentimes extremely long legs (Machado et al. 2007). The all-time fossils are once more those of the Rhynie cherts, which preserve the internal beefcake, including specimens that take the reproductive organs of either males or females (Dunlop et al. 2003). Their morphology suggests that they are essentially modern in grade. The fact that the Devonian species was placed in one of the four major living groups of Opiliones (Dunlop et al. 2004) implies that harvestmen were amongst the earliest branching arachnids and corroborates contempo molecular work suggesting a relatively early Paleozoic radiation in the group (Giribet et al. 2010). Furthermore, the fact that they have remained morphologically largely unchanged for over 400 million years suggests that they exemplify evolutionary stasis. Why this is the example remains unclear, just this uncertainty regarding the cause of stasis in no way undermines evolution as a god-of-the-gaps proponent would suggest. Stasis within species is expected in a number of evolutionary models (Eldredge and Gould 1972; Sheldon 1996; Benton and Pearson 2001). Thus, in higher-level taxonomic groups with relatively depression rates of speciation, nosotros may expect elements of stasis (run across give-and-take: Gould 2002, p. 936; Cavalier-Smith 2006, p. 999; and stasis in ecological assemblages: DiMichele et al. 2004). It is noteworthy, however, that stasis in taxonomic groups above the species level is the exception rather than the rule, as the in a higher place examples demonstrate. The fact that such stasis exists presents u.s.a. with a compelling opportunity to explain its presence—it does not let a non-naturalistic view to win by default.

Terrestrial Adaptations

Only nine of 58 extinct and extant beast phyla have terrestrial representatives (Labandeira and Beall 1990), largely considering land presents a new and hostile environment for a marine organism (Selden and Jeram 1989; Selden and Edwards 1990). As a event, life on land requires a suite of adaptations. The presence of such changes to accommodate a new mode of life provides excellent evidence for evolution; they accept a clear functional significance, and a number have evolved separately in dissimilar lineages (Raven 1985). To reiterate, the earliest known terrestrial animals were arthropods (Petty 1983)—members of the Myriapoda (millipedes, centipedes, and their kin), Arachnida (spiders, scorpions, and relatives), and Hexapoda (insects and three smaller, primitively wingless groups). In this, the final department of the paper, we shall provide an overview of the adaptations nowadays in terrestrial arthropod groups and then outline why their convergent evolution (independent origins in different lineages) has sometimes complicated efforts to appraise arthropod relationships (Edgecombe 2010).

Water Loss

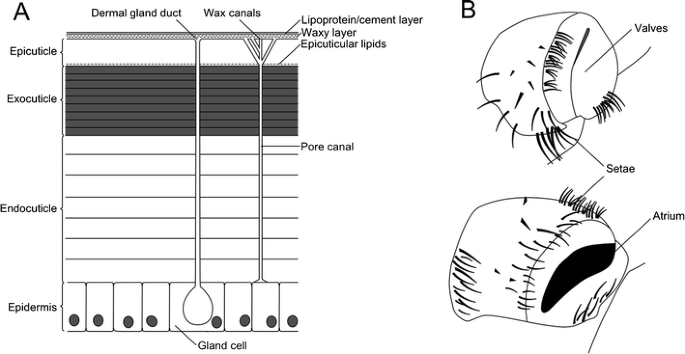

Of the issues associated with terrestrial life, perchance the biggest is that of water memory (Hadley 1994). H2o is a vital solvent for life, and minimizing water loss and ensuring its availability is vital for terrestrial organisms (Petty 1983). A major part of the fight to avoid desiccation is the arthropods' exoskeleton, the outermost layer of which (the epicuticle) is waxy and waterproof (Fig. 5a; Cody et al. 2011). This proofing is caused by lipids (hydrocarbons, in this instance including methane series-similar molecules, wax esters, fat acids, and ketones) both inside the epicuticle and deposited on its surface (Hadley 1986). As well every bit waterproofing an organism, this very successfully prevents evaporation. As we shall see below, terrestrial arthropods employ a variety of independently derived respiratory systems. Despite these independent origins, all are internal, an arrangement which serves to lessen water loss (Brusca and Brusca 2003). Additionally, all possess spiracles (Fig. 5b)—the structures that provide the earliest show for fully terrestrial life in millipedes. Spiracles act as an opening through the cuticle into respiratory structures, and—despite contained origins—those of insects (Gullan and Cranston 2010), myriapods (Shear and Edgecombe 2010), and chelicerates (Levi 1967) have associated musculature to regulate gas entry and exit, and minimize h2o loss through the moist respiratory structures. This is even the case where the respiratory organs—introduced below—differ greatly, for instance, between the book lungs of scorpions (Polis 1990) and the tracheal system of insects (Grimaldi and Engel 2005).

a Structure of arthropod cuticle showing the four primary layers and fine structure of the surface. Likewise shown are vertical channels—dermal gland ducts extending from the epidermis and secreting an every bit even so unknown substance and pore/wax canals which carry lipids from the epidermis to the epicuticle. Subsequently Hadley (1986). b Spiracles of a cockroach, shown closed (top) and open (bottom). After Bell and Adiyodi (1982)

Another major source of water loss in organisms is excretion. When animals digest protein, backlog nitrogen is produced and is normally liberated in the form of ammonia (NH3), a toxic compound that requires rapid dilution or removal (Brusca and Brusca 2003). Dilution demands abundant water and is thus unsuitable for terrestrial organisms, for whom water is a precious resource. Thus, virtually terrestrial organisms convert ammonia into more complex yet less toxic compounds; in vertebrates, similar us, urea, just in arthropods uric acid is more common, which is ofttimes precipitated in solid grade (Raven 1985). In arthropods, this waste is removed with the aid of two types of organs.

Nephridia are organs found on i or a few anterior torso segments of all arthropod groups. The closest living relatives of arthropods, the velvet worms (Onychophora), have a pair of nephridia on almost body segments, and they resemble those of many aquatic animals (Fig. 6a) in being composed of an excretory duct starting at the animal'southward exterior (opening to a pore at the inner base of each leg in velvet worms) and ending with a funnel-shaped, hair-lined opening into the trunk. The hairs direct fluid into the duct (Ruppert et al. 2003). As this moves through, the reabsorption and secretion of cells lining the duct modify the liquid, concentrating waste products (Ruppert and Smith 1988; Campiglia and Maddrell 1986; Bartolomaeus 1992). Waste is excreted to the outside through the terminal opening, known as the nephridopore. Nephridia of arthropods, in the form of coxal glands, antennal glands, maxillary glands, or labial kidneys (depending on where they are located), differ in being internally closed and the funnel is not ciliated. Nephridial organs are thought to accept been present in the concluding common antecedent of all arthropods (known as a plesiomorphic trait).

a Example of a nephridium showing both cilia to directly fluid into the nephridial tube and resorptive cells that concentrate waste products. b Diagram showing Malpighian tubules, with arrows showing the movement of waste and food, and the cycling of water in the system. Both based on diagrams in Barnes et al. (2001)

Most terrestrial arthropods also possess or wholly replace nephridia with structures known as Malpighian tubules, which let efficient waste material removal. These are blind ducts which open at ane end into the gut and remain unattached at the other stop (Fig. 6b). They float and move around in arthropods' blood-filled body cavity (or hemocoel) and blot waste products. Equally the waste moves downward the tubule, water is reabsorbed, until crystals of uric acid are formed, and in the hindgut, farther reabsorption occurs in a structure known every bit the rectal gland (Roberts 1986). The above description is based upon the Malpighian tubules of insects, and each individual tin can have hundreds of these (Brusca and Brusca 2003). However, very similar structures have been independently derived in both myriapods, which take only one or two depending on the group (Hopkin and Read 1992; Lewis 2007), and terrestrial chelicerates, which take several branching tubules (Barnes et al. 2001). Water loss can farther be reduced through behavior—arthropods at take chances of desiccation volition oft live in humid and moist environments to the extent that some extract moisture from the substrate (Crawford and Cloudsley-Thompson 1971). Many desert-dwelling house species avert periods of high temperatures by condign inactive in burrows (Hadley 1974).

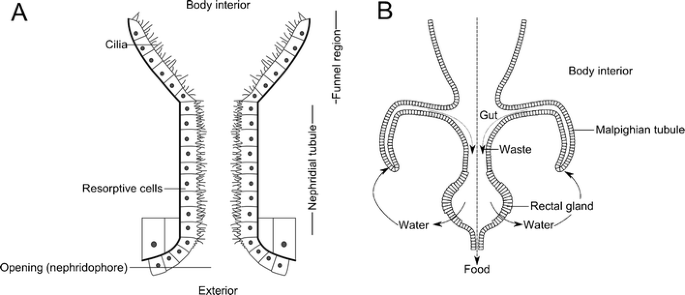

Gas Exchange

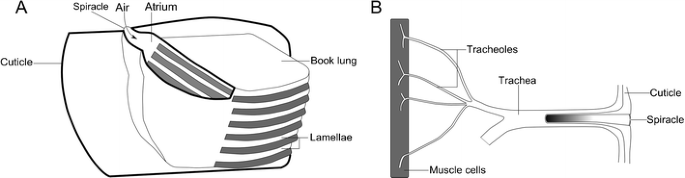

Another major issue with life on land is that of respiration, or gas commutation (Raven 1985). This cannot be washed through increasing the permeability of the exoskeleton, which would allow significant h2o loss. As we have seen, this is a pregnant consideration, and all only the smallest terrestrial arthropods have specialized gas exchange structures (Selden and Edwards 1990). These come in 2 flavors. The first—found in arachnids—are the book lungs: stacked, blood-filled lamellae extending into an air-filled cavity (Fig. 7a). This cavity (the atrium) opens to the outside through the spiracles (Scholtz and Kamenz 2006), and the thin lamellae provide a high surface area to let gas exchange. The second blazon of respiratory structures, which probably evolved convergently in insects and myriapods (Grimaldi 2010), are known as tracheae (Fig. 7b). These are branching cuticle-lined tubules opening externally through the spiracles and terminating internally in the blood, or organ tissues (Barnes et al. 2001). This is an efficient system, allowing straight gas substitution with the internal organs and blood—so much and then that a like system has secondarily evolved from book lungs in some spiders (Schmitz and Perry 2001). Comparable structures called pseudotrachea are also establish in woodlice, which are crustaceans of the order Isopoda (Edney 1968).

a Simplified diagram showing an arachnid book lung. In reality, these accept tens of lamellae. Afterward Levi (1967). b The tracheal morphology of insects. After Brusca and Brusca (2003)

Reproduction

A less immediately credible issue is that of reproduction—for arthropods in the marine realm, releasing eggs and sperm into the bounding main for external fertilization is a viable arroyo for reproduction (Selden and Jeram 1989). This is non as constructive in the terrestrial realm, however, and internal fertilization is usually preferred. Associated with this is a wide range of complex sperm transfer techniques—for example, the use of packages of sperm known every bit spermatophores is common, protecting them (to an extent) from the harsh terrestrial surroundings. A bewilderingly vast array of sometimes complex courtship behaviors has developed in terrestrial arthropods (Choe and Crespi 1997). While there are myriad possible causes for this adaptation (Bastock 2007), in part this could exist to ensure the successful transfer of spermatophores (for case, in the whip spiders, Fig. 2a; Weygoldt 2002). Direct sperm transfer in the class of copulation bypasses the risk of environmental damage in many more than derived forms (Selden and Edwards 1990). Young are frequently helped with parental brooding during embryonic evolution or after birth (Labandeira and Beall 1990).

Locomotion and Senses

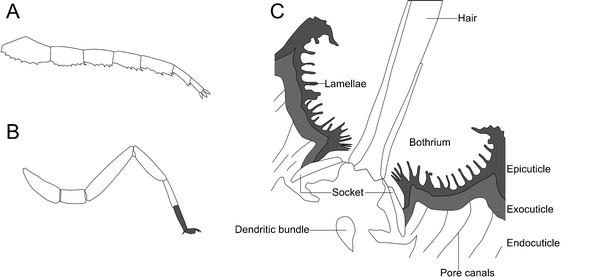

While life on state presents a plethora of other challenges, the concluding we volition look at hither stem from the physical differences between h2o and air. These can accept a significant impact on an organism's morphology, given that water has greater buoyancy than air (Selden and Jeram 1989). To support themselves, terrestrial organisms require rigid skeletal elements, and the arthropods had a preexisting advantage in their presence of an exoskeleton (Raven 1985). Terrestrial arthropods also generally adopt a more than stable hanging stance, standing on the underside of their limbs whose ends are at a low angle to the ground (a plantigrade tarsus; Størmer 1970; Fig. 8a). There are besides a huge number of sensory adaptations to this new medium, for example, the trichobothria of scorpions (Fig. 8b)—long, sparse hairs originating in a cup-shaped depression that can sense very slight air vibrations (Reissland and Görner 1985). This aids casualty location and orientation relative to air current, but would non work in a fluid medium (Krapf 1986; Meßlinger 1987). Superficially similar trichobothria are too present in some myriapods (Haupt 1979); the distant human relationship between these myriapods and arachnids indicates a convergent development of trichobothria.

a Instance of a digitigrade stance based on the limbs of trilobites. Afterward Størmer (1963). b A plantigrade stance based on the limbs of extant scorpions, the plantigrade segments of the limb termination in grey. After Størmer (1963). c Cantankerous-department through a scorpion bothrium showing the sensory hair and socket in which it sits, iii layers of the cuticle, and the pore canals. Likewise of note are the sensory dendritic package and lamellae. After Meßlinger (1987)

As a result of this suite of adaptations—and a host of further physiological changes—arthropods are successful terrestrial organisms. Then successful, in fact, that whether judged past number of species or individuals, they are thriving desert inhabitants (Edney 1967) and are vital members of these harshest terrestrial ecosystems (Whitford 2000).

Uncertainty

All of these evolutionary adaptations increase fettle in terrestrial environments, and as such, their parallel (convergent) evolution in multiple lineages under the same selective pressure is expected. However, they also effectively demonstrate a major cause of uncertainty amongst arthropod workers—the traditional footing for assessing evolutionary relationships is morphology (Darwin 1859; Skelton 1993). Thus, assessing whether structures are homologous (share a mutual origin) or homoplasious (the result of convergence) is vital to understanding a grouping's relationships (Edgecombe 2009). This is rarely clear-cut, however. To use examples we have seen already, insects and myriapods share tracheae and Malphighian tubules, and these features were traditionally ascribed to inheritance from common ancestry because insects and myriapods were considered sister taxa in a grouping known as the Atelocerata (Snodgrass 1938; Klass and Kristensen 2001; Bitsch and Bitsch 2004; encounter too word in Shultz and Regier 2000 and Dohle 1998). They farther share a suite of other characters, including unmarried-branched appendages and a caput comprising an antennal segment, a limbless (intercalary) segment, and and so two segments bearing mouthparts. Even so, DNA analysis has never supported this group, with many different kinds of genetic data all agreeing instead that the insects share a mutual ancestor with the crustaceans (insects and crustaceans collectively forming a group called the Tetraconata; Jenner 2010). This is at present largely accepted and has been corroborated past many features of the brain, optics, and nervous system development that are unique to insects and crustaceans merely not shared by myriapods (Edgecombe 2010). The evolutionary pic provided past the genes and nervous system suggests that tracheae and Malphighian tubules in insects and myriapods are an instance of convergent development in ii terrestrial lineages. However, the new consensus on an insect–crustacean human relationship emerged from twenty years of enquiry (including enormous technological and theoretical advances in molecular biological science and new techniques of investigating beefcake) and through frank discussion of the opposing arguments.

This process of altering hypotheses on the basis of increased evidence is central to the science, however such advances rely on uncertainty and debate. If god-of-the-gaps creationist opposition makes scientists reluctant to limited their doubts on a bailiwick—such equally the issue of arthropod relationships outlined hither—these advances would be slower-to-nonexistent. Due to the nature of evolution, ambiguity is ubiquitous; the outlined instance of similarity equally a result of either a common evolutionary origin or afterward convergence is just one of many sources of contend. It is for this reason that myriad unanswered questions regarding arthropod phylogeny remain, some at a fairly basic level. To present unanswered questions as a weakness, or pretend they undermine evidence, is disingenuous and incorrect. Rather, the possibility of new testify, resulting in paradigm shifts and a greater agreement of the history of life, is one of the most exciting elements of science.

References

-

Anderson LI, Trewin NH. An Early on Devonian arthropod fauna from the Windyfield Cherts, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Palaeontology. 2003;46(three):467–509.

-

Barnes RSK, Calow PP, Olive PJW, Golding DW, Spicer JI. The invertebrates: a synthesis. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2001.

-

Bartolomaeus T. Protonephridia and metanephridia—their relation within the Bilateria. J Zool Syst Evol Research 1992;30:21–45.

-

Bastock M. Courtship: an ethological study. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers; 2007.

-

Bell WJ, Adiyodi KG. The American cockroach. London: Chapman and Hall; 1982.

-

Benton MJ. Vertebrate palaeontology: tertiary edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2005.

-

Benton MJ, Pearson PN. Speciation in the fossil record. Trends Ecol Evol. 2001;16(7):405–11.

-

Béthoux O, Klass KD, Schneider JW. Tackling the Protoblattoidea problem: revision of Protoblattinopsis stubblefieldi (Dictyoptera; Belatedly Carboniferous). European J Entomol. 2009;106:145–52.

-

Bitsch C, Bitsch J. Phylogenetic relationships of basal hexapods amid the mandibulate arthropods: a cladistic analysis based on comparative morphological characters. Zool Scr. 2004;33(vi):511–50.

-

Brusca RC, Brusca GJ. Invertebrates—2d edition. Sunderland: Sinauer Assembly; 2003.

-

Campiglia SS, Maddrell SHP. Ion absorption by the distal tubules of onychophoran nephridia. J Exp Biol. 1986;121:43–54.

-

Cavalier-Smith T. Cell evolution and Earth history: stasis and revolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B: Biol Sci. 2006;361(1470):969–1006.

-

Chandler Jr AD. Anthracite coal and the ancestry of the Industrial Revolution in the United States. Bus Hist Rev. 1972;46(ii):147–81.

-

Choe JC, Crespi BJ. The evolution of mating systems in insects and arachnids. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997.

-

Clack JA. The emergence of early tetrapods. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2006;232(2–4):167–89.

-

Clack JA. The fin to limb transition: new information, interpretations, and hypotheses from paleontology and developmental biology. Annu Rev World Planet Sci. 2009;37(1):163–79.

-

Cleal CJ, Thomas BA. Palaeozoic tropical rainforests and their result on global climates: is the by the cardinal to the present? Geobiology. 2005;iii(ane):13–31.

-

Coates MI, Ruta M, Friedman M. Ever since Owen: changing perspectives on the early on evolution of tetrapods. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2008;39:571–92.

-

Cocks LRM, Torsvik Th. European geography in a global context from the Vendian to the finish of the Palaeozoic. Geol Soc Lond, Memoirs. 2006;32(1):83–95.

-

Cody GD, Gupta NS, Briggs DEG, Kilcoyne ALD, Summons RE, Kenig F, et al. Molecular signature of chitin–protein circuitous in Paleozoic arthropods. Geology. 2011;39(iii):255–8.

-

Crawford CS. Millipedes equally model detritivores. Berichte der Naturwissenschaftlich. 1992;ten:277–88.

-

Crawford CS, Cloudsley-Thompson JL. Water relations and desiccation-fugitive behavior in the vinegaroon Mastigoproctus giganteus (Arachnida: Uropygi). Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 1971;fourteen(1):99–106.

-

Curtis CD, Coleman ML. On the precipitation of early diagenetic calcite, dolomite and siderite concretions in complex depositional sequences. In: Gautier DL, editor. Roles of organic matter in sediment diagenesis. Guild of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists Special Publication 38; 1986. p. 23–33.

-

Darwin C. On the origin of species by means of natural choice, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: John Murray; 1859.

-

Davies NS, Rygel MC, Gibling MR. Marine influence in the Upper Ordovician Juniata Formation (Potters Mills, Pennsylvania): implications for the history of life on country. Palaios. 2010;25(eight):527–39.

-

DiMichele WA. Chapter 1.3.eight.—Carboniferous coal-swamp forests. In: Briggs DEG, Crowther PR, editors. Palaeobiology II. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2001. p. 79–82.

-

DiMichele WA, Behrensmeyer AK, Olszewski TD, Labandeira CC, Pandolfi JM, Fly SL, et al. Long-term stasis in ecological assemblages: evidence from the fossil record. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2004;35(1):285–322.

-

DiMichele WA, Falcon-Lang HJ, John Nelson W, Elrick SD, Ames PR. Ecological gradients within a Pennsylvanian mire forest. Geology. 2007;35(5):415–8.

-

Dohle W. Myriapod-insect relationships as opposed to an insect–crustacean sister grouping relationship. In: Fortey RA, Thomas RH, editors. Arthropod relationships. London: Chapman & Hall; 1998. p. 305–15.

-

Dunlop JA. The origins of tetrapulmonate volume lungs and their significance for chelicerate phylogeny. In: Selden PA, editor. Proceedings of the 17th European Colloquium of Arachnology, Edinburgh 1997. Burnham Beeches: British Arachnological Club; 1997. p. nine–16.

-

Dunlop JA. Geological history and phylogeny of Chelicerata. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2010;39(2–three):124–42.

-

Dunlop JA, Webster M. Fossil evidence, terrestrialization and arachnid phylogeny. J Arachnol. 1999;27(1):86–93.

-

Dunlop JA, Anderson LI, Kerp H, Hass H. Preserved organs of Devonian harvestmen. Nature. 2003;425:916.

-

Dunlop JA, Anderson LI, Kerp H, Hass H. A harvestman (Arachnida: Opiliones) from the Early Devonian Rhynie cherts, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Trans Royal Soc Edinburgh, Earth Sci. 2004;94(4):341–54.

-

Dunlop JA, Tetlie OE, Penney D, Anderson LI. How many species of fossil arachnids are there? J Arachnol. 2008a;36(2):267–72.

-

Dunlop JA, Tetlie OE, Prendini L. Reinterpretation of the Silurian scorpion Proscorpius osborni (Whitfield): integrating data from Palaeozoic and recent scorpions. Palaeontology. 2008b;51(2):303–twenty.

-

Edgecombe GD. Palaeontological and molecular show linking arthropods, onychophorans, and other Ecdysozoa. Evol: Educ Outreach. 2009;2(2):178–90.

-

Edgecombe GD. Arthropod phylogeny: an overview from the perspectives of morphology, molecular information and the fossil record. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2010;39:74–87.

-

Edney EB. Water balance in desert arthropods. Scientific discipline. 1967;156(3778):1059–66.

-

Edney EB. Transition from water to state in isopod crustaceans. Amer Zool. 1968;eight(three):309–26.

-

Edwards D. The role of mid-Palaeozoic mesofossils in the detection of early bryophytes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B: Biol Sci. 2000;355:733–54.

-

Eldredge Due north, Gould SJ. Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism. In: Schopf TJ, editor. Models in paleobiology. San Francisco: Freeman, Cooper & Co.; 1972. p. 82–115.

-

Engel MS, Grimaldi DA. New calorie-free shed on the oldest insect. Nature. 2004;427:627–30.

-

Falcon-Lang HJ. Fire ecology of the Carboniferous tropical zone. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2000;164:339–55.

-

Falcon-Lang HJ, Miller RF. Palaeoenvironments and palaeoecology of the Early on Pennsylvanian Lancaster Formation ('Fern Ledges') of Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada. J Geol Soc Lond. 2007;164(five):945–57.

-

Fayers SR, Trewin NH. A hexapod from the Early on Devonian Windyfield chert, Rhynie, Scotland. Palaeontology. 2005;48(5):1117–30.

-

Fayers SR, Dunlop JA, Trewin NH. A new Early Devonian trigonotarbid arachnid from the Windyfield Chert, Rhynie, Scotland. J Syst Palaeontol. 2005;two(4):269–84.

-

Garwood RJ, Dunlop JA. Morphology and systematics of Anthracomartidae (Arachnida: Trigonotarbida). Palaeontology. 2011;54(1):145–61.

-

Garwood RJ, Sutton Physician. Ten-ray micro-tomography of Carboniferous stem-Dictyoptera: new insights into early insects. Biol Lett. 2010;6:699–702.

-

Garwood RJ, Dunlop JA, Sutton MD. High-fidelity Ten-ray micro-tomography reconstruction of siderite-hosted Carboniferous arachnids. Biol Lett. 2009;5:841–4.

-

Giribet G, Vogt 50, González AP, Abel PG, Prashant S, Kury AB. A multilocus approach to harvestman (Arachnida: Opiliones) phylogeny with emphasis on biogeography and the systematics of Laniatores. Cladistics. 2010;26(4):408–37.

-

Gould SJ. The structure of evolutionary theory. Cambridge: Belknap; 2002.

-

Gould SJ, Eldredge N. Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology. 1977;3(2):115–51.

-

Gradstein FM, Ogg JG, Smith AG. International stratigraphic nautical chart. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press; 2009.

-

Grimaldi DA. 400 million years on six legs: on the origin and early evolution of Hexapoda. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2010;39:191–203.

-

Grimaldi DA, Engel MS. Evolution of the insects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

-

Gullan PJ, Cranston PS. The insects: an outline of entomology—fourth edition. Oxford: Blackwell; 2010.

-

Hadley NF. Adaptational biological science of desert scorpions. J Arachnol. 1974;2:11–23.

-

Hadley NF. The arthropod cuticle. Sci Am. 1986;255:104–12.

-

Hadley NF. Water relations of terrestrial arthropods. London: Academic; 1994.

-

Hartwell Thousand. The First Industrial Revolution. The American Economic Review, vol. 57. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing; 1967.

-

Haupt J. Phylogenetic aspects of recent studies on myriapod sense organs. In: Camatini M, editor. Myriapod biology. London: Academic; 1979. p. 391–406.

-

Higashi M, Abe T, Burns TP. Carbon–nitrogen balance and termite ecology. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B: Biol Sci. 1992;249(1326):303–8.

-

Hopkin SP, Read HJ. The biological science of millipedes. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press; 1992.

-

Inward D, Beccaloni G, Eggleton P. Decease of an order: a comprehensive molecular phylogenetic study confirms that termites are eusocial cockroaches. Biol Lett. 2007;3:331–v.

-

Jenner RA. Higher-level crustacean phylogeny: consensus and alien hypotheses. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2010;39:143–53.

-

Jeram AJ. Scorpions from the Viséan of East Kirkton, Westward Lothian, Scotland, with a revision of the infraorder Mesoscorpionina. Trans Imperial Soc Edinburgh, Earth Sci. 1994a;84:283–99.

-

Jeram AJ. Carboniferous Orthosterni and their human relationship to living scorpions. Palaeontology. 1994b;37(3):513–50.

-

Jeram AJ, Selden PA, Edwards D. Country animals in the Silurian: Arachnids and myriapods from Shropshire, England. Science. 1990;250:658–61.

-

Johnson EW, Briggs DEG, Suthren RJ, Wright JL, Tunnicliff SP. Non-marine arthropod traces from the subaerial Ordovician Borrowdale volcanic group, English Lake Commune. Geol Mag. 1994;131(3):395–406.

-

Kamenz C, Dunlop JA, Scholtz Thou, Kerp H, Hass H. Microanatomy of Early Devonian volume lungs. Biol Lett. 2008;4:212–5.

-

Kenrick P, Crane PR. The origin and early development of plants on land. Nature. 1997;389:33–9.

-

Klass KD, Kristensen NP. The ground plan and affinities of hexapods: contempo progress and open problems. Annales de la Société Entomologique de France. 2001;37(1–2):265–98.

-

Krapf D. Verhaltensphysiologishe Untersuchungen zum Beutefang von Skorpionen mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Trichobothrien. PhD thesis, Academy of Würzburg; 1986.

-

Labandeira CC, Beall BS. Arthropod terrestriality. In: Culver SJ, editor. Arthropod palaeobiology. Brusk Courses in Palaeontology Number Iii. Knoxville: Palaeontological Society; 1990. p. 214–32.

-

Legg DA, Garwood RJ, Dunlop JA, and Sutton MD. A taxonomic revision of Orthosternous scorpions from the English Coal-Measures aided past 10-ray micro-tomography. Palaeontologia Electronica; 2011 (in press).

-

Levi HW. Adapations of respiratory systems of spiders. Development. 1967;21(3):571–83.

-

Lewis JGE. The biological science of centipedes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

-

Fiddling C. The colonisation of land: origins and adaptations of terrestrial animals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing; 1983.

-

Lourenço WR, Gall JC. Fossil scorpions from the Buntsandstein (Early on Triassic) of France. Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2004;3(v):369–78.

-

Machado G, Pinto-da-Rocha R, Giribet Grand. What are harvestmen? In: Pinto-da-Rocha R, Machado G, Giribet One thousand, editors. Harvestmen: the biology of Opiliones. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2007. p. 1–13.

-

Meßlinger K. Fine structure of scorpion trichobothria (Arachnida, Scorpiones). Zoomorphology. 1987;107(1):49–57.

-

Modesto SP, Hirst S, Reisz RR. Arthropod remains in the oral cavities of fossil reptiles support inference of early on insectivory. Biol Lett. 2009;v:838–40.

-

Nelson CE. On the persistence of unicorns: the trade-off between content and disquisitional thinking revisited. In: Pescosolido BA, Aminzade R, editors. The social worlds of higher education: handbook for education in a new century. Chiliad Oaks: Pino Forge Press; 1999. p. 168–84.

-

Norton RA, Bonamo PM, Grierson JD, Shear WA. Oribatid mite fossils from a terrestrial Devonian eolith near Gilboa, New York. J Paleontol. 1988;62(2):259–69.

-

Pennock RT. God of the gaps: the argument from ignorance and the limits of methodological naturalism. In: Petto AJ, Godfrey LR, editors. Scientists confront intelligent blueprint and creationism. New York: Westward.W. Norton; 2007. p. 309–38.

-

Plotnick RE, Kenig F, Scott Air-conditioning, Glasspool IJ, Eble CF, Lang WJ. Pennsylvanian paleokarst and cave fills from northern Illinois, United states of america: a window into Late Carboniferous environments and landscapes. PALAIOS. 2009;24(10):627–37.

-

Polis GA. The biology of scorpions. Palo Alto: Stanford University Printing; 1990.

-

Prave AR. Life on land in the Proterozoic: evidence from the Torridonian rocks of northwest Scotland. Geology. 2002;30:811–4.

-

Rasmussen B, Blake TS, Fletcher IR, Kilburn MR. Evidence for microbial life in synsedimentary cavities from 2.75 Ga terrestrial environments. Geology. 2009;37(5):423–6.

-

Raven JA. Comparative physiology of plant and arthropod land adaptation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B: Biol Sci. 1985;309(1138):273–88.

-

Reissland A, Görner P. Trichobothria. In: Barth FG, editor. Neurobiology of arachnids. Berlin: Springer; 1985. p. 138–61.

-

Retallack GJ. Scoyenia burrows from Ordovician palaeosols of the Juniata Formation in Pennsylvania. Palaeontology. 2001;44(2):209–35.

-

Retallack GJ, Feakes C. Trace fossil evidence for Tardily Ordovician animals on country. Science. 1987;235:61–three.

-

Rice CM, Ashcroft WA, Batten DJ, Boyce AJ, Caulfield JBD, Fallick AE, et al. A Devonian auriferous hot leap system, Rhynie, Scotland. J Geol Soc Lond. 1995;152(ii):229–50.

-

Roberts MBV. Biological science: a functional arroyo—4th Edition. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes; 1986.

-

Rößler R, Dunlop JA, Schneider JW. A redescription of some poorly known Rotliegend arachnids from the Lower Permian (Asselian) of the Ilfeld and Thuringian Wood Basins, Germany. Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 2003;77(ii):417–27.

-

Ruppert EE, Smith PR. The functional organization of filtration nephridia. Biol Rev. 1988;63(2):231–58.

-

Ruppert EE, Trick R, Barnes RD. Invertebrate zoology: a functional evolutionary approach—7th edition. Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole; 2003.

-

Sahney S, Benton MJ. Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B: Biol Sci. 2008;275:759–65.

-

Schawaller Due west, Shear WA, Bonamo PM. The get-go Paleozoic pseudoscorpions (Arachnida, Pseudoscorpionida). Am Mus Novit. 1991;3009:1–17.

-

Schmitz A, Perry SF. Bimodal breathing in jumping spiders: morphometric partitioning of the lungs and tracheae in Salticus scenicus (Arachnida, Araneae, Salticidae). J Exp Biol. 2001;204(24):4321–34.

-

Scholtz 1000, Kamenz C. The book lungs of Scorpiones and Tetrapulmonata (Chelicerata, Arachnida): show for homology and a single terrestrialisation issue of a common arachnid ancestor. Zoology. 2006;109:2–xiii.

-

Scott EC. Evolution vs. creationism: an introduction—second edition. Westport: Greenwood Press; 2009.

-

Selden PA, Edwards D. Colonisation of the land. In: Allen KC, Briggs DEG, editors. Evolution and the fossil record. London: Belhaven Press; 1990. p. 122–52.

-

Selden PA, Jeram AJ. Palaeophysiology of terrestrialisation in the Chelicerata. Trans Royal Soc Edinburgh, World Sci. 1989;eighty:303–10.

-

Selden PA, Shear WA, Bonamo PM. A spider and other arachnids from the Devonian of New York, and reinterpretations of Devonian Araneae. Palaeontology. 1991;34(two):241–81.

-

Shear WA. Gigantocharinus szatmaryi, a new trigonotarbid arachnid from the Late Devonian of N America (Chelicerata: Arachnida: Trigonotarbida). J Paleontol. 2000a;74(1):25–31.

-

Shear WA. The early evolution of terrestrial ecosystems. Nature. 2000b;351:283–9.

-

Shear WA, Bonamo PM. Devonobiomorpha, a new order of centipeds (Chilopoda) from the Middle Devonian of Gilboa, New York State, USA, and the phylogeny of centiped orders. Am Mus Novit. 1988;2927:one–xxx.

-

Shear WA, Edgecombe GD. The geological tape and phylogeny of the Myriapoda. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2010;39:174–90.

-

Shear WA, Kukalová-Peck J. The ecology of Paleozoic terrestrial arthropods: the fossil show. Can J Zool. 1990;68(9):1807–34.

-

Shear WA, Selden PA. Rustling in the undergrowth: animals in early on terrestrial ecosystems. In: Gensel PG, Edwards D, editors. Plants invade the country: evolutionary and environmental perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press; 2001. p. 29–51.

-

Shear WA, Bonamo PM, Grierson JD, Rolfe WDI, Smith EL, Norton RA. Early on land animals in North America: Evidence from Devonian age arthropods from Gilboa, New York. Scientific discipline 1984;224(4648):492–4.

-

Shear WA, Selden PA, Rolfe WDI, Bonamo PM, Grierson JD. New terrestrial arachnids from the Devonian of Gilboa, New York (Arachnida: Trigonotarbida). Am Mus Novit. 1987;2901:1–74.

-

Shear WA, Gensel PG, Jeram AJ. Fossils of big terrestrial arthropods from the Lower Devonian of Canada. Nature. 1996;384:555–87.

-

Shear WA, Jeram AJ, Selden PA. Centiped legs (Arthropoda, Chilopoda, Scutigeromorpha) from the Silurian and Devonian of Great britain and the Devonian of North America. Am Mus Novit. 1998;3231:1–xvi.

-

Sheldon P. Plus ça modify—a model for stasis and evolution in different environments. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 1996;127:209–27.

-

Shultz JW, Regier JC. Phylogenetic assay of arthropods using two nuclear protein-encoding genes supports a crustacean/hexapod clade. Proc R Soc Lond Series B: Biol Sci. 2000;267:1011–nine.

-

Skelton P. Development: a biological and palaeontological approach. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1993.

-

Snodgrass RE. Development of the Annelida: Onychophora and Arthropoda. Smithson Misc Collect. 1938;97(6):one–159.

-

Størmer 50. Arthropods from the Lower Devonian (Lower Emsian) of Alken an der Mosel, Germany. Part 1: Arachnida. Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 1970;51:335–69.

-

Størmer L. Arthropods from the Lower Devonian (Lower Emsian) of Alken an der Mosel, Frg. Part 2: Xiphosura. Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 1972;53:i–29.

-

Størmer L. Arthropods from the Lower Devonian (Lower Emsian) of Alken an der Mosel, Federal republic of germany. Part 3: Eurypterida, Hughmilleriidae. Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 1973;54:119–205.

-

Størmer L. Arthropods from the Lower Devonian (Lower Emsian) of Alken an der Mosel, Germany. Part four: Eurypterida, Drepanopteridae, and other groups. Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 1974;54:359–451.

-

Størmer L. Arthropods from the Lower Devonian (Lower Emsian) of Alken an der Mosel, Germany. Function 5. Myriapods and additional forms, with general remarks on the fauna and problems regarding invasion of land by arthropods. Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 1976;57:87–183.

-

Størmer 50. Gigantoscorpio willsi, a new scorpion from the Lower Carboniferous of Scotland and its associated preying microorganisms. Skrifter Utgitt av Det Norske Videnskaps–Akademi I Oslo I. Mathematisk-Naturvidenskabelig Klasse 1963; 8:i–171.

-

Strother PK, Battison L, Brasier MD, Wellman CH. Earth's earliest non-marine eukaryotes. Nature. 2011;473:505–ix.

-

Trewin NH, Fayers SR. A new crustacean from the Early Devonian Rhynie Chert, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Trans Royal Soc Edinburgh, Globe Sci. 2007;93(4):355–82.

-

Trewin NH, Fayers SR, Kelman R. Subaqueous silicification of the contents of modest ponds in an Early Devonian hot-leap complex, Rhynie, Scotland. Can J Earth Sci. 2003;40(eleven):1697–712.

-

Vogel BR, Durden CJ. The occurrence of stigmata in a Carboniferous scorpion. J Paleontol. 1966;40(3):655–8.

-

Wellman CH, Gray J. The microfossil record of early land plants. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Serial B: Biol Sci. 2000;355(1398):717–31.

-

Wellman CH, Kerp H, Hass H. Spores of the Rhynie chert plant Aglaophyton (Rhynia) major (Kidston and Lang) D.S. Edwards, 1986. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 2006;142(3–four):229–l.

-

Weygoldt P. Fighting, courtship, and spermatophore morphology of the whip spider Musicodamon atlanteus Fage, 1939 (Phrynichidae) (Chelicerata, Amblypygi). Zoologischer Anzeiger. 2002;241(3):245–54.

-

Whitford WG. Keystone arthropods as webmasters in desert ecosystems. In: Coleman DC, Hendrix PF, editors. Invertebrates as webmasters in ecosystems. Wallingford: CABI; 2000. p. 25–41.

-

Wilson HM. Juliformian millipedes from the Lower Devonian of Euramerica: implications for the timing of millipede cladogenesis in the Paleozoic. J Paleontol. 2006;lxxx:638–49.

-

Wilson HM, Anderson LI. Morphology and taxonomy of Paleozoic millipedes (Diplopoda:Chilognatha: Archipolypoda) from Scotland. J Paleontol. 2004;78(1):169–84.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This is an open admission article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original writer(s) and source are credited.

Reprints and Permissions

Most this article

Cite this article

Garwood, R.J., Edgecombe, G.D. Early Terrestrial Animals, Evolution, and Doubt. Evo Edu Outreach 4, 489–501 (2011). https://doi.org/x.1007/s12052-011-0357-y

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y

Keywords

- Terrestrialisation

- Development

- Arthropods

- Palaeozoic ecosystems

Source: https://evolution-outreach.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y

Posted by: cottowhinsed.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Was The First Class Of Animals To Move From Water To Land"

Post a Comment